|

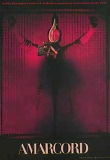

THE FILM  Federico Fellini's warmly nostalgic memory piece examines daily life in the Italian village of Rimini during the reign of Mussolini, and won the 1974 Academy Award as Best Foreign Film. The film's greatest asset is its ability to be sweet without being cloying, due in great part to Danilo Donati's surrealistic art direction and to the frequently bawdy injections of sex and politics by screenwriters Fellini and Tonino Guerra. Fellini clearly has deep affection for the people of this seaside village, warts and all, and communicates it through episodic visual anecdotes which are seen as if through the mists of a favorite dream, playfully scored by Nino Rota and lovingly photographed by Giuseppe Rotunno. Amarcord is a rich gem of a film which only improves on subsequent viewings. Federico Fellini's warmly nostalgic memory piece examines daily life in the Italian village of Rimini during the reign of Mussolini, and won the 1974 Academy Award as Best Foreign Film. The film's greatest asset is its ability to be sweet without being cloying, due in great part to Danilo Donati's surrealistic art direction and to the frequently bawdy injections of sex and politics by screenwriters Fellini and Tonino Guerra. Fellini clearly has deep affection for the people of this seaside village, warts and all, and communicates it through episodic visual anecdotes which are seen as if through the mists of a favorite dream, playfully scored by Nino Rota and lovingly photographed by Giuseppe Rotunno. Amarcord is a rich gem of a film which only improves on subsequent viewings.

Amarcord is the phonetic translation of the Italian words "Mi Ricordo" (I remember) as pronounced in the dialect of Emilia-Romagna, the birthplace of director Federico Fellini and the setting of this wonderful film. Little surprise, then, that it is a poignant and bawdy semi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale, with an ethereal, dreamlike quality that combines sharply drawn memories with vividly engaging fantasy. Like William Wordsworth, Fellini implies that the child is father to the man, and Amarcord is a both a lament for and an homage to his hometown. Employing a picaresque style, Fellini expertly weaves the tales of a wild menagerie of characters in pre-WW II Italy. No mere sentimentalist, he also tackles the prickly issue of the emergence of Fascism. The film takes careful aim at fanatics, while conserving its empathy for the lost, questing, confused, and lonely individuals in its midst. The family at the center of it all, loosely based on Fellini's own, is a well-drawn melange of coarse, pathetic, colorful, clever, and cranky characters. While Fellini does not choose nostalgic sepia tones, he does shoot much of the film in muted colors that seem slightly out-of-focus, as if he were attempting to transport us into a dreamlike state. Blending scenes of pathos and humor, vulgar carnal desire and transcendent magical illumination (the peacock's standing in the newly fallen snow, spreading its magnificent plumage is this film's signature image), Amarcord [...] remains a triumph of personal filmmaking. semi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale, with an ethereal, dreamlike quality that combines sharply drawn memories with vividly engaging fantasy. Like William Wordsworth, Fellini implies that the child is father to the man, and Amarcord is a both a lament for and an homage to his hometown. Employing a picaresque style, Fellini expertly weaves the tales of a wild menagerie of characters in pre-WW II Italy. No mere sentimentalist, he also tackles the prickly issue of the emergence of Fascism. The film takes careful aim at fanatics, while conserving its empathy for the lost, questing, confused, and lonely individuals in its midst. The family at the center of it all, loosely based on Fellini's own, is a well-drawn melange of coarse, pathetic, colorful, clever, and cranky characters. While Fellini does not choose nostalgic sepia tones, he does shoot much of the film in muted colors that seem slightly out-of-focus, as if he were attempting to transport us into a dreamlike state. Blending scenes of pathos and humor, vulgar carnal desire and transcendent magical illumination (the peacock's standing in the newly fallen snow, spreading its magnificent plumage is this film's signature image), Amarcord [...] remains a triumph of personal filmmaking.

Fellini at his ripest and loudest recreates a fantasy-vision of his home town during the fascist period. With generous helpings of soap opera and burlesque he generally gets his better effects by orchestrating his colourful cast of characters around the town square, on a boat outing, or at a festive wedding. When he narrows his focus down to individual groups, he usually limits himself to corny bathroom and bedroom jokes, which produce the desired titters but little else. But despite the ups and downs, it’s still Fellini which has become an identifiable substance like salami or pepperoni that can be sliced into at any point yielding pretty much the same general consistency and flavour. Fellini at his ripest and loudest recreates a fantasy-vision of his home town during the fascist period. With generous helpings of soap opera and burlesque he generally gets his better effects by orchestrating his colourful cast of characters around the town square, on a boat outing, or at a festive wedding. When he narrows his focus down to individual groups, he usually limits himself to corny bathroom and bedroom jokes, which produce the desired titters but little else. But despite the ups and downs, it’s still Fellini which has become an identifiable substance like salami or pepperoni that can be sliced into at any point yielding pretty much the same general consistency and flavour.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, TimeOut

Twenty years after I Vitelloni, Fellini returned to Rimini. In Amarcord he calls on the free-spirited fantasies of his later films, as well as the bittersweet comedy and intimate sense of detail of his early films, to evoke a year in the life of this small Italian coastal town in the mid-1930s. Amarcord is filled with phantasmagorical gems from the director's imagination: a peacock flying through the snow alights on the piazza to signal the coming of spring; a child on his way to school encounters a herd of cows who are transformed by the early-morning fog into frightening monsters. But the film is also rooted in history, filtered through memory: focusing on one family of perfectly normal eccentrics, Fellini examines their impact on each other's lives and the impact of life on them through a series of interacting tales ("some romantic, some slapstick, some elegiacal, some bawdy, some … mysterious" Vincent Canby). Fascism was a fact of life and, for Fellini, a focal point around which to examine the community, the Church, the state and the family–all of the elements that made Mussolini's acceptance possible. Like his protagonist Titta, a man in his fifties in 1972, Fellini looks to the past in this film for "the source of our illusions, our innocence and our feelings." But for Fellini, it is also a catharsis: "I made Amarcord to finish with youth and tenderness," he has commented. Twenty years after I Vitelloni, Fellini returned to Rimini. In Amarcord he calls on the free-spirited fantasies of his later films, as well as the bittersweet comedy and intimate sense of detail of his early films, to evoke a year in the life of this small Italian coastal town in the mid-1930s. Amarcord is filled with phantasmagorical gems from the director's imagination: a peacock flying through the snow alights on the piazza to signal the coming of spring; a child on his way to school encounters a herd of cows who are transformed by the early-morning fog into frightening monsters. But the film is also rooted in history, filtered through memory: focusing on one family of perfectly normal eccentrics, Fellini examines their impact on each other's lives and the impact of life on them through a series of interacting tales ("some romantic, some slapstick, some elegiacal, some bawdy, some … mysterious" Vincent Canby). Fascism was a fact of life and, for Fellini, a focal point around which to examine the community, the Church, the state and the family–all of the elements that made Mussolini's acceptance possible. Like his protagonist Titta, a man in his fifties in 1972, Fellini looks to the past in this film for "the source of our illusions, our innocence and our feelings." But for Fellini, it is also a catharsis: "I made Amarcord to finish with youth and tenderness," he has commented.

[...] Der Film ist kein objektiver Bericht, sondern ein durch Erinnerungen verändertes und verwandeltes Zeitbild, in dem der Satiriker Fellini seiner Phantasie und Vorliebe fürs Groteske freien Lauf läßt — eine bildmächtige Schau des vielfältigen, abgrundtief häßlichen wie unendlich schönen Lebens. Lexikon des internationalen Films

Federico Fellini's semi-autobiographical AMARCORD is a funny, moving, and extremely entertaining mosaic of colorful comic and sexual vignettes, beautifully made by a master caricaturist.

[...] With AMARCORD, Fellini dropped all pretense of presenting a coherent plot, in favor of the impressionistic stylization and anecdotal narratives that had been increasingly dominating his work since the mid-60s. Never has the gallery of Fellini's cartoonish grotesqueries been more prevalent than in AMARCORD, from the hilariously feuding Biondi family with its irascible father, suicidal mother, crazy uncle, horny grandfather, and mischievous sons, to the motley group of local eccentrics—the blind, accordion-playing beggar; the bragging pushcart vendor; the elegant cinema manager called "Ronald Colman"; and of course, the marvelous assortment of women who are the objects of Titta's and his friend's fantasies—Volpina the animalistic whore, the Sophia Loren-ish Gradisca, and the freakishly endowed tobacconist, who has what's possibly the film's funniest scene, when she whips out her mammoth breasts to the astonishment of Titta, and the poor boy is practically suffocated by them and ends up sick in bed. Fellini takes all of these characters and creates a wonderfully riotous fresco of lust, vulgarity, and low comedy, yet infuses the various episodes with a sense of nostalgic lyricism, recalling the carefree days of innocent youth, when American movies overshadowed even Fascism and dominated one's dreams. (The local theatre is filled with pictures of Laurel and Hardy, Norma Shearer, et al., and Gradisca goes to see BEAU GESTE, and fantasizes about finding her own Gary Cooper.) [...] With AMARCORD, Fellini dropped all pretense of presenting a coherent plot, in favor of the impressionistic stylization and anecdotal narratives that had been increasingly dominating his work since the mid-60s. Never has the gallery of Fellini's cartoonish grotesqueries been more prevalent than in AMARCORD, from the hilariously feuding Biondi family with its irascible father, suicidal mother, crazy uncle, horny grandfather, and mischievous sons, to the motley group of local eccentrics—the blind, accordion-playing beggar; the bragging pushcart vendor; the elegant cinema manager called "Ronald Colman"; and of course, the marvelous assortment of women who are the objects of Titta's and his friend's fantasies—Volpina the animalistic whore, the Sophia Loren-ish Gradisca, and the freakishly endowed tobacconist, who has what's possibly the film's funniest scene, when she whips out her mammoth breasts to the astonishment of Titta, and the poor boy is practically suffocated by them and ends up sick in bed. Fellini takes all of these characters and creates a wonderfully riotous fresco of lust, vulgarity, and low comedy, yet infuses the various episodes with a sense of nostalgic lyricism, recalling the carefree days of innocent youth, when American movies overshadowed even Fascism and dominated one's dreams. (The local theatre is filled with pictures of Laurel and Hardy, Norma Shearer, et al., and Gradisca goes to see BEAU GESTE, and fantasizes about finding her own Gary Cooper.)

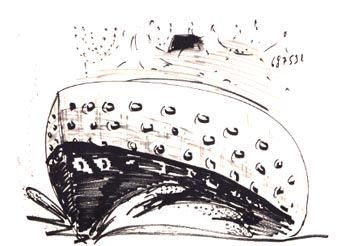

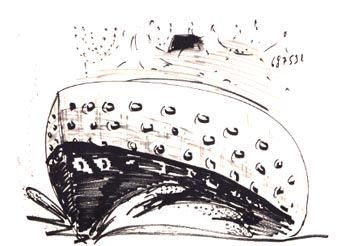

Filmed almost entirely on the soundstages and backlots of Cinecitta, the film is a triumph of studio artifice, with Fellini and his brilliant production designer Danilo Danoti and cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno creating a world of fanciful memory, producing one fantastic and poetic image after another: the Fascist rally with its gigantic "Il Duce" face made of flowers; the car bouncing up and down and its headlights flickering on and off as the boys masturbate and scream Jean Harlow's name; the row of female derrieres wiggling onto bicycle seats; the Arabian Nights fantasy with the 30 concubines in the swimming pool; the magical appearance of the luxury liner, with its twinkling lights set against a studio sunset; the peacock landing in the snow and displaying its dazzling plumage; and the wind blowing puffballs through the sky, which opens and closes the film. Poured on top of all this, like a fine sauce over delicious pasta, is one of Nino Rota's loveliest, bounciest scores, resulting in what is undoubtedly one of Fellini's greatest films. Filmed almost entirely on the soundstages and backlots of Cinecitta, the film is a triumph of studio artifice, with Fellini and his brilliant production designer Danilo Danoti and cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno creating a world of fanciful memory, producing one fantastic and poetic image after another: the Fascist rally with its gigantic "Il Duce" face made of flowers; the car bouncing up and down and its headlights flickering on and off as the boys masturbate and scream Jean Harlow's name; the row of female derrieres wiggling onto bicycle seats; the Arabian Nights fantasy with the 30 concubines in the swimming pool; the magical appearance of the luxury liner, with its twinkling lights set against a studio sunset; the peacock landing in the snow and displaying its dazzling plumage; and the wind blowing puffballs through the sky, which opens and closes the film. Poured on top of all this, like a fine sauce over delicious pasta, is one of Nino Rota's loveliest, bounciest scores, resulting in what is undoubtedly one of Fellini's greatest films.

While Fellini’s works from Amarcord to the present are consistently interpreted by the critics as segments of the director’s autobiography, Fellini himself has consistently declared that Amarcord, Casanova (1976), Prova d’orchestra (1979), and La città delle donne (1980) have important sociological and political dimensions as well. Thus, while Amarcord was enthusiastically received as a nostalgic return to the world of the vitelloni in Fellini’s early works, the director’s goals were very different:

"The province of Amarcord is one in which we are all recognizable, the director first of all, in the ignorance which confounded us. A great ignorance and a great confusion. Not that I wish to minimize the economic and social causes of fascism. I only wish to say that today what is still most interesting is the psychological, emotional manner of being a fascist. What is this manner? It is a sort of blockage, an arrested development during the phase of adolescence… That is, this remaining children for eternity, this leaving responsibilities for orhers, this living with the comforting sensation that there is someone who thinks for you (and at one time it’s mother, then it’s father, then it’s the mayor, anoeher time Il Duce, another time the Madonna, another time the Bishop, in short other people): and in the meanwhile you have this limited, time-wasting freedom which permies you only to cultivate absurd dreams–the dream of the American cinema, or the Oriental dream concerning women; in conclusion, the same old, monstrous, out-of-date myths that even today seem to me to form the most imporeant conditioning of the average Italian." "The province of Amarcord is one in which we are all recognizable, the director first of all, in the ignorance which confounded us. A great ignorance and a great confusion. Not that I wish to minimize the economic and social causes of fascism. I only wish to say that today what is still most interesting is the psychological, emotional manner of being a fascist. What is this manner? It is a sort of blockage, an arrested development during the phase of adolescence… That is, this remaining children for eternity, this leaving responsibilities for orhers, this living with the comforting sensation that there is someone who thinks for you (and at one time it’s mother, then it’s father, then it’s the mayor, anoeher time Il Duce, another time the Madonna, another time the Bishop, in short other people): and in the meanwhile you have this limited, time-wasting freedom which permies you only to cultivate absurd dreams–the dream of the American cinema, or the Oriental dream concerning women; in conclusion, the same old, monstrous, out-of-date myths that even today seem to me to form the most imporeant conditioning of the average Italian."

All of the collective events in the provincial town during the Mussolinian era–the absurd classrooms taught by pedantic, incompetent, or neurotic professors; the visit of the Fascist federale on April 21 (the anniversary of the mythical foundation of Rome celebrated by the regime); the passage of the ocean liner Rex before an awed group of townspeople; the burning of the great bonfire to celebrate the pagan rites of springtime–are, for Fellini, "occasions of total stupidity," part of a gigantic leveling process which buries individuality in mass conformity before symbols of power. This is clearest in the imaginary Fascist wedding staged by Fellini before an enormous bust of Mussolini made of pink and white flowers: the entire population seems anxious to become a collective, unthinking entity under Il Duce’s benevolent gaze. All of the collective events in the provincial town during the Mussolinian era–the absurd classrooms taught by pedantic, incompetent, or neurotic professors; the visit of the Fascist federale on April 21 (the anniversary of the mythical foundation of Rome celebrated by the regime); the passage of the ocean liner Rex before an awed group of townspeople; the burning of the great bonfire to celebrate the pagan rites of springtime–are, for Fellini, "occasions of total stupidity," part of a gigantic leveling process which buries individuality in mass conformity before symbols of power. This is clearest in the imaginary Fascist wedding staged by Fellini before an enormous bust of Mussolini made of pink and white flowers: the entire population seems anxious to become a collective, unthinking entity under Il Duce’s benevolent gaze.

Yet central to Fellini’s view of Italy’s collective past is his own complicity in this experience and his attempts to come to grips with it in his memory. His critical vision of provincial life also has its poignant side: the poetic arrival of the puff balls signaling the change of the seasons; the Hollywood characters, townspeople resembling American movie stars, that dominate the village’s mentality; the sympathetic Gradisca (Magali Noel), who swoons before the Rex, the federale, or other symbols of the regime’s power and eventually marries a patriotic policeman who shouts "Viva l’Italia!" at their wedding; the adventures of the young Titta (Bruno Zanin) as he discovers his nascent sexuality in the cinema or with the buxom tobacconist in town; the outbursts of Titta’s neurotic mother against his honest and hardworking ex-Socialist father. These poetic sequences touch us in a manner that the political argument of Amarcord could never do, for they uncover the sense of loss and unrealized potential we all share, even if we have never experienced the same social structure that permeated Italian life during Mussolini’s day. But it is a profoundly negative vision, one which underlines at every opportunity the disastrous effects such a society had upon the individual and his self-expression.

If we accept Fellini’s assertion, as I believe we must, that he and his films are obsessed with the liberation of the individual, then it is legitimate to inquire of him whether he has anything but negative visions to offer us. What does Fellini propose to counter the cultural void repeatedly reflected in so many of his recent films? I believe Fellini’s answer–the positive, life-affirming message of his works– lies precisely in the image of the liberated creative individual, in creativity itself. What his cinema can provide, not only by his example but also in specific films, is the image of the completely liberated creator. Peter Bondanella:

Italian Cinema From Neorealism to the Present

New York 1983, p. 248-251

Fellini während der Dreharbeiten

Rimini ist ein verwickelter, beängstigender, zärtlicher Mischmasch mit großem Atem, mit der weiten Öffnung des Meeres. Dort wird unser Heimweh klar und durchsichtig, vor allem vor dem winterlichen Meer mit den weißen Wellenkämmen und dem starken Wind…

Heimatstolz spricht aus diesen Worten. Fellini fühlt sich ganz als Romagnole: Wir haben keine Krämerseelen. Eher poetische. Unsere Rinder sind weiß wie Schnee — es ist nicht wahr, daß Weiß leichter schmutzt als Gelb —, und ihre sehr langen Hörner haben die Form einer Lyra. Es sind sensible, musikalische Tiere.

Als der Regisseur in der Krise steckte und eine Zwangspause einlegen mußte, schrieb er den Essay Mein Rimini. Es ist ein sehr persönliches Buch, voller Kindheitserinnerungen, Anekdoten und Konfessionen. Aber auch mit exakten Ortsangaben, so daß man auf den Spuren Fellinis einen Rundgang durch die Stadt unternehmen kann. Vom Bahnhof, dem Ort der abenteuerlichen Träume, zum eleganten, um die Jahrhundertwende erbauten 'Grand Hotel', einem Märchen des Reichtums, des Luxus, des orientalischen Prunks, oder gleich zum Strand, wo die TouristenMassen in der Sonne braten. Nach dem Krieg, in dem viel zerstört wurde, ist Rimini zu einer gesichtslosen Ferien-Hochburg verkommen, doch schon als kleiner Junge beobachtete Fellini die Deutschen, die mit dem Daimler Benz ans Meer kamen (und im Wasser Dickwänste, Walrosse). Die eigentliche Stadt liegt auf der anderen Seite der Eisenbahnlinie. Das Kino 'Fulgor', das Federico in hitzigen Pubertätsträumen eine warme Kloake aller Laster schien, steht noch; es befindet sich gleich neben der Kirche Chiesa dei Servi. Seine Angaben über das Geburtshaus sind jedoch zu korrigieren: Laut Eintragung in die Einwohnermeldekartei wohnte die Familie Fellini damals in der Viale Dardanelli Nr. 10. Derlei Recherchen finden nicht den Beifall des Künstlers, der mit seinem Werk keineswegs den Fremdenverkehr ankurbeln will: Ich habe den Eindruck, zu einem Objeict des Tourismus geworden zu sein, dagegen lehne ich mich auf. Als der Regisseur in der Krise steckte und eine Zwangspause einlegen mußte, schrieb er den Essay Mein Rimini. Es ist ein sehr persönliches Buch, voller Kindheitserinnerungen, Anekdoten und Konfessionen. Aber auch mit exakten Ortsangaben, so daß man auf den Spuren Fellinis einen Rundgang durch die Stadt unternehmen kann. Vom Bahnhof, dem Ort der abenteuerlichen Träume, zum eleganten, um die Jahrhundertwende erbauten 'Grand Hotel', einem Märchen des Reichtums, des Luxus, des orientalischen Prunks, oder gleich zum Strand, wo die TouristenMassen in der Sonne braten. Nach dem Krieg, in dem viel zerstört wurde, ist Rimini zu einer gesichtslosen Ferien-Hochburg verkommen, doch schon als kleiner Junge beobachtete Fellini die Deutschen, die mit dem Daimler Benz ans Meer kamen (und im Wasser Dickwänste, Walrosse). Die eigentliche Stadt liegt auf der anderen Seite der Eisenbahnlinie. Das Kino 'Fulgor', das Federico in hitzigen Pubertätsträumen eine warme Kloake aller Laster schien, steht noch; es befindet sich gleich neben der Kirche Chiesa dei Servi. Seine Angaben über das Geburtshaus sind jedoch zu korrigieren: Laut Eintragung in die Einwohnermeldekartei wohnte die Familie Fellini damals in der Viale Dardanelli Nr. 10. Derlei Recherchen finden nicht den Beifall des Künstlers, der mit seinem Werk keineswegs den Fremdenverkehr ankurbeln will: Ich habe den Eindruck, zu einem Objeict des Tourismus geworden zu sein, dagegen lehne ich mich auf.

Federico Fellini hat ein gebrochenes Verhältnis zum Heimatort. Ich kehre nicht gern nach Rimini zurück, bekennt er. Dort leben die Mutter, Schwester Maddalena und ein paar Jugendfreunde, mit denen er immer noch Kontakt hält. Aber jedesmal, wenn er die Stätten der Kindheit aufsucht, wird er von Gespenstern angefallen, die eigentlich schon archiviert, eingeordnet sind. Rimini ist für ihn eine verfälschte, manipulierte, erfundene Erinnerung. Und so soll es bleiben: Offenbar hat er Angst davor, von der Wirklichkeit zur Korrektur seines Bildes gezwungen zu werden. Erinnerung ist eine subjektive Wahrheit; Fellini will sie nicht der Realität aussetzen. Den Film Amarcord — der Titel zitiert einen Dialektausdruck, eine Verschleifung von 'A m’arcord', auf deutsch: 'Ich erinnere mich' — hat er nicht in Rimini gedreht. Im Atelier ließ er die Kleinstadt-Szenerie nachbauen. Heimat: ein Kunstprodukt, hergestellt in Cinecittà.

Die Reise in die Dimension der Erinnerung ist ein in der Vergangenheit spielender Tagtraum, notwendigerweise eine verrückte, lächerliche, komische und närrische Wiederbesichtigung von Situationen, Erlebnissen und Wahrnehmungen, die, oft nur unzusammenhängend, verzerrt und verzeichnet, aus dem Unbewußten auftauchen. Die erste Szene von Amarcord: Corso und Piazza eines Städtchens. Der Frühling kündigt sich an. Durch die Luft wirbelt die Manine, flockig-weicher Pappelsamen. Der Dorfdepp schnappt nach ihm, brabbelt eine unverständliche Erklärung vor sich hin. Was willst du uns sagen? Aus dem Off hört man Fellinis Stimme, die Erinnerung beschwörend. Statt einer durchgehenden Handlung entfaltet der Film ein Kleinstadt-Panorama als pittoresken Bilderbogen: der Provinzgigolo und der klatschsüchtige Friseur, die mondäne Schönheit und der skurrile Sonderling, die italienische Familie, in der laut und tennperamentvoll gestritten wird, Lehrer, Geistliche und Carabinieri, allesamt leicht groteske Gestalten, liebevoll gezeichnete Karikaturen. Die Provinz als Welttheater: Man spielt große Oper, doch es wirkt immer nur wie eine Operettenvorstellung. Der Junge Titta steht im Mittelpunkt, seine pubertären Träume und Sehnsüchte, diese seltsam erregenden und zugleich quälenden Momente, verwirrend und peinlich. Der Reiz des Verbotenen, die ersten sexuellen Abenteuer und hinterher die Schuldgefühle. Dabei spielt sich das meist nur in Gedanken ab. Als die Tabakhändlerin ihn an ihren gewaltigen Busen drückt, flüchtet er entsetzt zur Mama. Eine andere Episode variiert das Thema: Man unternimmt eine Landpartie, dazu wird der verrückte Onkel Theo aus der Anstalt geholt. In einem unbeobachteten Moment klettert er auf einen Baum und schreit: Ich will eine Frau. Anfangs amüsiert man sich darüber, doch nach einer Stunde stellt sich Ratlosigkeit ein. Vergeblich alle Versuche, ihn herunterzuholen — der Onkel sitzt in der Baumkrone und verlangt nach einer Frau. Erst als die zwergwüchsige Nonne aus der Anstalt kommt — sie verfügt über eine unerklärliche Macht —, genügt ein Satz, und der eben noch wütende Irre steigt gehorsam und sanftmütig vom Baum. Die Reise in die Dimension der Erinnerung ist ein in der Vergangenheit spielender Tagtraum, notwendigerweise eine verrückte, lächerliche, komische und närrische Wiederbesichtigung von Situationen, Erlebnissen und Wahrnehmungen, die, oft nur unzusammenhängend, verzerrt und verzeichnet, aus dem Unbewußten auftauchen. Die erste Szene von Amarcord: Corso und Piazza eines Städtchens. Der Frühling kündigt sich an. Durch die Luft wirbelt die Manine, flockig-weicher Pappelsamen. Der Dorfdepp schnappt nach ihm, brabbelt eine unverständliche Erklärung vor sich hin. Was willst du uns sagen? Aus dem Off hört man Fellinis Stimme, die Erinnerung beschwörend. Statt einer durchgehenden Handlung entfaltet der Film ein Kleinstadt-Panorama als pittoresken Bilderbogen: der Provinzgigolo und der klatschsüchtige Friseur, die mondäne Schönheit und der skurrile Sonderling, die italienische Familie, in der laut und tennperamentvoll gestritten wird, Lehrer, Geistliche und Carabinieri, allesamt leicht groteske Gestalten, liebevoll gezeichnete Karikaturen. Die Provinz als Welttheater: Man spielt große Oper, doch es wirkt immer nur wie eine Operettenvorstellung. Der Junge Titta steht im Mittelpunkt, seine pubertären Träume und Sehnsüchte, diese seltsam erregenden und zugleich quälenden Momente, verwirrend und peinlich. Der Reiz des Verbotenen, die ersten sexuellen Abenteuer und hinterher die Schuldgefühle. Dabei spielt sich das meist nur in Gedanken ab. Als die Tabakhändlerin ihn an ihren gewaltigen Busen drückt, flüchtet er entsetzt zur Mama. Eine andere Episode variiert das Thema: Man unternimmt eine Landpartie, dazu wird der verrückte Onkel Theo aus der Anstalt geholt. In einem unbeobachteten Moment klettert er auf einen Baum und schreit: Ich will eine Frau. Anfangs amüsiert man sich darüber, doch nach einer Stunde stellt sich Ratlosigkeit ein. Vergeblich alle Versuche, ihn herunterzuholen — der Onkel sitzt in der Baumkrone und verlangt nach einer Frau. Erst als die zwergwüchsige Nonne aus der Anstalt kommt — sie verfügt über eine unerklärliche Macht —, genügt ein Satz, und der eben noch wütende Irre steigt gehorsam und sanftmütig vom Baum.

Die Filme haben jetzt die Phase der erzählenden Prosa hinter sich gelassen und kommen der Poesie immer näher. Einige ausdrucksstarke Bilder sind die eigentlichen Schlüsselszenen. An einem nebligen Morgen steht dem kleinen Bruder Tittas auf dern Schulweg plötzlich ein weißes Fabeltier gegenüber — oder ist es nur eins der heimischen Rinder mit den wie eine Lyra gebogenen Hörnern? An einem Tag im Sommer wartet die ganze Stadt in Ruderbooten auf den Ozeanriesen 'Rex'. Es wird Nacht. und dann passiert der lichtergeschmückte Luxusdampfer die Mole — ein illuminiertes Raumschiff, das gleich wieder von der Dunkelheit geschluckt wird. Gebannt verfolgt man das Schauspiel: Das Schiff kommt aus Amerika, eine Ahnung von großer Welt und unerreichbarer Ferne zieht vorüber. Zugleich ist die 'Rex' ein Repräsentationsobjekt mit Propagandawert, ein Symbol für den faschistischen Staat und seine Macht. Die Filme haben jetzt die Phase der erzählenden Prosa hinter sich gelassen und kommen der Poesie immer näher. Einige ausdrucksstarke Bilder sind die eigentlichen Schlüsselszenen. An einem nebligen Morgen steht dem kleinen Bruder Tittas auf dern Schulweg plötzlich ein weißes Fabeltier gegenüber — oder ist es nur eins der heimischen Rinder mit den wie eine Lyra gebogenen Hörnern? An einem Tag im Sommer wartet die ganze Stadt in Ruderbooten auf den Ozeanriesen 'Rex'. Es wird Nacht. und dann passiert der lichtergeschmückte Luxusdampfer die Mole — ein illuminiertes Raumschiff, das gleich wieder von der Dunkelheit geschluckt wird. Gebannt verfolgt man das Schauspiel: Das Schiff kommt aus Amerika, eine Ahnung von großer Welt und unerreichbarer Ferne zieht vorüber. Zugleich ist die 'Rex' ein Repräsentationsobjekt mit Propagandawert, ein Symbol für den faschistischen Staat und seine Macht.

Bereits in der ersten Sequenz, als die Filmkamera den Ort durchstreift, kommt ein kahlköpfiger Faschist ins Bild. Neben den traditionellen Festen, die den Wechsel der Jahreszeiten begleiten, gibt es auch die vom Regime verordneten oder in seinem Sinn umfunktionierten Feiern. Mit militärischem Pomp wird der 21. April, der Jahrestag der Gründung Roms, inszeniert. Es kommt zu einem Zwischenfall: Unbekannte haben auf dem Kirchturm ein Grammophon installiert, das ununterbrochen die 'Internationale' abspielt; auch Tittas Vater wird von den wütenden Faschisten malträtiert. Uber dieser und manch anderer Episode liegt der Faschismus wie ein drohender Schatten. Er wird verscheucht von anderen, ebenso abenteuerlichen Ereignissen. Der Erzählfluß ebnet alles ein: In der Erinnerung werden politische Konfrontationen zu Anekdoten, die man genüßlich erzählen kann wie Schulstreiche oder erste Liebeserlebnisse. Verharmlosung des Faschismus hat man Fellini vorgeworfen.

Tatsächlich bemüht sich der Film nicht darum, politische und sozioökonomische Zusammenhänge aufzuzeigen. Er bleibt auf einer rein phänomenologischen Ebene; die Perspektive ist der Blick eines Kindes. Fellini über Mussolini: Und dann hat er den Gymnastiklehrer erfunden. Das verzeihe ich ihm nie. Diese Erfindung hat mir zu hart zugesetzt. Der Arbeitstitel von Amarcord lautete 'Il borgo', 'Das Städtchen', und der Ort sollte modellhaft für die italienische Provinz stehen. Eine Gemeinde, fernab von den großen Zentren, selbstgenügsam in sich ruhend und ohne viel Kontakt mit der Außenwelt. Daß am Schluß die Kleinstadt-Schönheit sich nach auswärts verheiratet, ist eine Sensation — wie kann nur jemand freiwillig seine Heimat verlassen? Fellini zeigt, wie beschränkt das Provinzdasein ist: Es war eine verfehlte, klägliche, schäbige, grausame Welt. Der Provinzler weigert sich, erwachsen zu werden. und diese Haltung hat fatale politische Konsequenzen: Man lebt in dem tröstlichen Gefühl, daß immer jemand da ist, der für einen denkt, einmal ist es die Mama, einmal der Papa, bald der Duce, die Madonna oder der Bischof. Unterwürfigkeit und Infantilismus sind die zwei Seiten einer Medaille. Und ich glaube, Schuld an diesem chronischen Entwicklungsfehler, diesem Steckenbleiben in einem kindlichen Stadium, hat mehl noch als der Faschismus die katholische Kirche. Tatsächlich bemüht sich der Film nicht darum, politische und sozioökonomische Zusammenhänge aufzuzeigen. Er bleibt auf einer rein phänomenologischen Ebene; die Perspektive ist der Blick eines Kindes. Fellini über Mussolini: Und dann hat er den Gymnastiklehrer erfunden. Das verzeihe ich ihm nie. Diese Erfindung hat mir zu hart zugesetzt. Der Arbeitstitel von Amarcord lautete 'Il borgo', 'Das Städtchen', und der Ort sollte modellhaft für die italienische Provinz stehen. Eine Gemeinde, fernab von den großen Zentren, selbstgenügsam in sich ruhend und ohne viel Kontakt mit der Außenwelt. Daß am Schluß die Kleinstadt-Schönheit sich nach auswärts verheiratet, ist eine Sensation — wie kann nur jemand freiwillig seine Heimat verlassen? Fellini zeigt, wie beschränkt das Provinzdasein ist: Es war eine verfehlte, klägliche, schäbige, grausame Welt. Der Provinzler weigert sich, erwachsen zu werden. und diese Haltung hat fatale politische Konsequenzen: Man lebt in dem tröstlichen Gefühl, daß immer jemand da ist, der für einen denkt, einmal ist es die Mama, einmal der Papa, bald der Duce, die Madonna oder der Bischof. Unterwürfigkeit und Infantilismus sind die zwei Seiten einer Medaille. Und ich glaube, Schuld an diesem chronischen Entwicklungsfehler, diesem Steckenbleiben in einem kindlichen Stadium, hat mehl noch als der Faschismus die katholische Kirche.

Meine Erirmerungen sind nicht von Nostalgie, sondern von Ablehnung erfallt, behauptete Fellini in einem Interview zu Amarcord. Doch der Film widerspricht seinem Regisseur. Von der verbalen Radikalität, mit der er Provinzialismus geißelt, ist in Amarcord kaum etwas zu spüren. Der Filmautor strebte Ambivalenz an — Das Städtchen hat zwar etwas Erstickendes, andererseits ist es zugleich eine Arche Noah —, doch im Konflikt zwischen Erinnerung und Wirklichkeit siegte das Wunschbild. Im Gespräch nennt Fellini die Menge, die den vorbeiziehenden Ozeandampfer anstaunt, kindisch und dumm, aber die Inszenierung der Sequenz zeugt davon, daß der Regisseur nicht minder fasziniert zuschaut. Der Mann der Interviews hat seinen Heimatort für immer verlassen; der Filmschöpfer ist mit seinem Werk ganz nach Rimini zurückgekehrt. An der derben Komik und den lächerlichen Posen der Provinzler hat er offenbar seinen Spaß. Der Titel Amarcord ist eine poetische Chiffre, in der auch Amore anklingt: Die Welt der Provinz wird in ein liebevolles Licht getaucht. Meine Erirmerungen sind nicht von Nostalgie, sondern von Ablehnung erfallt, behauptete Fellini in einem Interview zu Amarcord. Doch der Film widerspricht seinem Regisseur. Von der verbalen Radikalität, mit der er Provinzialismus geißelt, ist in Amarcord kaum etwas zu spüren. Der Filmautor strebte Ambivalenz an — Das Städtchen hat zwar etwas Erstickendes, andererseits ist es zugleich eine Arche Noah —, doch im Konflikt zwischen Erinnerung und Wirklichkeit siegte das Wunschbild. Im Gespräch nennt Fellini die Menge, die den vorbeiziehenden Ozeandampfer anstaunt, kindisch und dumm, aber die Inszenierung der Sequenz zeugt davon, daß der Regisseur nicht minder fasziniert zuschaut. Der Mann der Interviews hat seinen Heimatort für immer verlassen; der Filmschöpfer ist mit seinem Werk ganz nach Rimini zurückgekehrt. An der derben Komik und den lächerlichen Posen der Provinzler hat er offenbar seinen Spaß. Der Titel Amarcord ist eine poetische Chiffre, in der auch Amore anklingt: Die Welt der Provinz wird in ein liebevolles Licht getaucht.

Die Distanz der Zeit wird mitinszeniert. Der Film wird wie ein Album werden, wie wenn man in einem alten Fotoalbum blättert, erläuterte Fellini während der Dreharbeiten. Bilder, Augenblicke. kein Held. Der Held ist ein Schatten, ist eine Hand, die Notizen macht, ein Finger, der auf den Auslöser der Kamera drückt, ein machtloser Zeuge, der, ohne selbst helfen zu können, der Auflösung einer Epache beiwohnt. Statt filmischer Vergegenwärtigung erstarrte Formen: In jedem Moment wird der Gestus der Erinnerung ausgestellt. Die eher gedämpften Farben, die an naive Malerei erinnernde Bildgestaltung, der Verzicht auf interessante Kameraperspektiven und die Bevorzugung flächiger Bildarrangements, der sprunghafte Rhythmus harter Schnittfolgen: Erzählduktus und optischer Stil arbeiten mit dem Mittel der Reduktion.

Michael Töteberg: Federico Fellini

Reinbek 1989, S. 88-94

While Roma takes Fellini’s adult home as its point of departure, Amarcord (1973)returns to the provincial world of Fellini’s youth and the kind of town we saw represented in I Vitelloni, only 20 years eadier With its foregrounding of Fascism, Amarcord would seem to suggest the latter response to the question posed at the end of Roma. Certainly the film marks a point at which the affirmative potential of Fellini’s preceding films disappears.

Like so many of Fellini’s films, Amarcord points backwards as well as forwards both formally and thematically. Ist suggests the kind of thematic and narrative unity present in pre-Roma films, and while its renunciation of creative possibility makes it a "late" film, its renunciation is accompanied by sadness and nostalgia rather than the resignation or ironic humor that mark Fellini’s final films. Amarcord’s tone of sadness is clearest in the concluding sequences: Miranda’s death and funeral and even Gradisca’s wedding celebration. A sense of nostalgia or loss is built into the narrative process, particularly as it is framed by the first and last social gatherings in the film: the burning of the witch of winter and the wedding party. The first takes place in the center of town and has a single unifying activity that, despite frequent divergences, focuses everyone’s energy. There is a strong sense of participation, a sense of promise (the end of winter/the coming of spring), and a sense of ritual in complicity with nature. Though the sequence offers some indication of negative things to come, we get the general impression of a community with at least some common purpose and a great capacity for fun. Moreover, there is a potential protagonist, the adolescent Titta, who is alert, active, and independent. and a sense of ritual in complicity with nature. Though the sequence offers some indication of negative things to come, we get the general impression of a community with at least some common purpose and a great capacity for fun. Moreover, there is a potential protagonist, the adolescent Titta, who is alert, active, and independent.

In contrast. the final gathering takes place in a barren field on the outskirts of town, where nature seems dead and alien rather than promising and complicit. A much smaller percentage of the town is gathered, and the sequence presents not the wedding (that is, the comma together) but the aftermath, which, despite moments of unity, is largely disjointed. The wedding itself is presented as a source of rupture, taking Gradisca away from the town. Community breakdown is poignantly represented when Gradisca throws her bouquet and it drops unceremoniously (in the fullest sense) to the ground. Titta is alienated, intoxicated, and marginal, relating to neither Gradisca nor his friends and showing none of his earlier capacity for adventure.

One of the clearest signs of fragmentation in Amarcord lies in its lack of a clearly defined central character. Though Titta is arguably the film’s most important figure, he is only one of several narrators, his voice-over is insignificant, he is missing from far more scenes than Encolpio in Fellini-Satyricon, and the film is rarely organized around his point of view. In fact, in terms of its multiple, discontinuous, and (as I will shortly elaborate) flawed narrators, Amarcord puts the lie to its own name. The title, in Romagnan dialect, means "I remember,’’ but there is no "I" who remembers, a "prevarication" that only draws attention to the absence of a single, organising, intelligence. One of the clearest signs of fragmentation in Amarcord lies in its lack of a clearly defined central character. Though Titta is arguably the film’s most important figure, he is only one of several narrators, his voice-over is insignificant, he is missing from far more scenes than Encolpio in Fellini-Satyricon, and the film is rarely organized around his point of view. In fact, in terms of its multiple, discontinuous, and (as I will shortly elaborate) flawed narrators, Amarcord puts the lie to its own name. The title, in Romagnan dialect, means "I remember,’’ but there is no "I" who remembers, a "prevarication" that only draws attention to the absence of a single, organising, intelligence.

Amarcord achieves its rather somber ending through what I perceive as a four-part progression: (1) relative social cohesion marked by events within the town, (2) increasing disunity and reliance on external forces, marked by a movement outside the town, (3) return to a town that has lost all internal cohesion and meaning, and (4) a concluding state of exile (or "eviction" or "evacuation," to use terms that apply elsewhere in Fellini’s work). One of the central issues of the film, harkening back to earlier Fellini films of failed individuation, is the absence or death of consciousness, particularly reflected in the problematic idealization of women.

Relative Cohesion At the beginning, Amarcord focuses on events and institutions central to the community: seasonal ritual, school, work, and Titta’s family. Though this might imply a good deal of conformity, there is also a great deal of rebelliousness. The latter makes for wonderful comedy in the school scenes and even in the home, where we discover that Titta has pissed on the hat of a local dignitary–no doubt an affront to the dignitary himself, but even more so, from what we see, to Titta’s father. All this begins to change with the film’s second evening gathering, which lacks a unifying event such as the witch-burning. The only thing that unites people in the course of the sequence is the arrival of the newest contingent of prostitutes who parade down the main street in a carriage.As the townspeople line the sidewalks to observe and in some cases ogle, participation gives way to witnessing, internally motivated activity to motivation from outside.

Of course, motivation from without has been evident from the opening scene, as the "puffs"–the swirling, floating seeds of springtimc occupy everyone’s attention and even control the narrative, ushering the camera eye from Titta’s house to the town square to the the feminine to serve as yet another symbol of male authority–as well as male lack.)

Consistent with all this, Gradisca idealizes not only Fascists but the prostitutes who ride through town, seeing in theman appropriate model of service to men. And the prostitutes, in turn, highlight the complicated position of women within the town and Italian Catholicism in general: simultaneously condemned and valorized for their sexuality, as their sexuality in turn becomes conflated with mothering. The visual paradox Amarcord offers in the second evening sequence store-window madonnas juxtaposed with the arrival of prostitutes–proves not so paradoxical after all, as the "fallen woman" can also be "ministering angel" or saint in the contorted Catholic logic of the feminine.

In the course of all this, women, idealisation, and ultimately Fascism all come to operate as spectacle and, more to the point, spectacle as the realm of missing power. Because women cannot exist physically or immediately for men (that is, as partners), they exist purely as visual objects. (Gradisca is turned into spectacle in her very first appearance: introduced beside a curtain then wiggling her derriere as a barber plays a flute.) As such, they are invested with enormous symbolic power. However, this power does not belong to them, as it is projected. And it ultimately makes men feel powerless, as it is larger than life. Once spectacle is discovered by men to be a place of power, they must usurp it–precisely the role played by Fascism with its massive parade and speeches accompanying Il Federale and the huge flowered mosaic of Mussolini.

In the course of all this, women, idealisation, and ultimately Fascism all come to operate as spectacle and, more to the point, spectacle as the realm of missing power. Because women cannot exist physically or immediately for men (that is, as partners), they exist purely as visual objects. (Gradisca is turned into spectacle in her very first appearance: introduced beside a curtain then wiggling her derriere as a barber plays a flute.) As such, they are invested with enormous symbolic power. However, this power does not belong to them, as it is projected. And it ultimately makes men feel powerless, as it is larger than life. Once spectacle is discovered by men to be a place of power, they must usurp it–precisely the role played by Fascism with its massive parade and speeches accompanying Il Federale and the huge flowered mosaic of Mussolini.

Though Fascism is initially presented as an instrument of unity, healing local divisiveness and gathering all the town under its sway, its arrival quickly prompts dissent, in the form of gunfire in the town square. An ensuing inquisition then causes a major rupture in Titta’s family. Aurelio (the father) is force-fed castor oil, returns home humiliated, loses dignity in the eyes of Titta, and denounces Lallo (his brother-in-law) as the one who turned him in. This is the last time we see the entire family together. Frank Burke: Fellini’s Films. From Postwar to Postmodern

New York 1996, p.206-208

The inhabitants of Fellini's imaginary Rimini are not divided into "good" anti-fascists and "evil" fascists. Instead, all of the characters are sketched out in masterful caricatures, comic types with antecedents in Fellini's earlier films. Fellini's fascists are not sinister, perverted individuals but pathetic clowns, manifestations of the arrested development typical of the entire village. As Fellini himself wrote in an essay-interview entitled "The Fascism Within Us": "I have the impression that fascism and adolescence continue to be ... permanent historical seasons of our lives ... remaining children for eternity, leaving responsibilities for others, living with the comforting sensation that there is someone who thinks for you ... and in the meanwhile, you have this limited, time-wasting freedom which permits you only to cultivate absurd dreams ..." Yet the hilarious portrait Fellini draws of the ridiculous parades, the gymnastic exercises in uniform, and the small daily compromises necessary to live under a dictatorship, speak volumes about what life was like in that era. Through the sequences in which the Amarcordians greet a visiting fascist bigwig and the one in which they row out in the sea to catch a glimpse of the passage of the Rex—an enormous ocean liner coming from America that was the pride of Mussolini's regime—Fellini reveals the mechanism behind the mimicry of the cinematic image, disclosing its function as a mediator of authentic sexual desire. These scenes ee the townspeople as dominated by false ideals and idiotic dreams of heroic feats and romantic love. Such public behavior has its direct psychological parallel in numerous scenes treating daily life at home, in schools, and in church with the clever comic touch that has always been Fellini's trademark.

More than any other Italian film's treatment of fascism, Fellini's Amarcord manages to explain the public lives of his characters by minute details of their private lives. The sense of intimacy and immediacy that the film creates allows the audience to recognize certain aspects of themselves in these characters. One of the most interesting stylistic features of Amarcord is its proliferation of narrative points of view. In the original Italian print, we discover a complex mixture of direct addresses to the camera by various characters, as well as voice-overs providing information or commentary on the film's action. In a few significant instances, this voice-over presence is provided by Fellini himself, something rendered moot when viewing prints dubbed in English. To define Amarcord as merely another "political" film would fail to do justice to such a poetic work. The film's title means "I remember" in one of the dialects of Fellini's native province, but this does not amount to a strictly autobiographical interpretation of work. While Amarcord, as its title suggests, contains a great deal of nostalgia, Fellini's use of nostalgia as a means of romanticizing the past serves to underline his belief that fascism was based upon false ideals, and also his recognition that regret or nostalgia is as inevitable as sentiment as refusal. More than any other Italian film's treatment of fascism, Fellini's Amarcord manages to explain the public lives of his characters by minute details of their private lives. The sense of intimacy and immediacy that the film creates allows the audience to recognize certain aspects of themselves in these characters. One of the most interesting stylistic features of Amarcord is its proliferation of narrative points of view. In the original Italian print, we discover a complex mixture of direct addresses to the camera by various characters, as well as voice-overs providing information or commentary on the film's action. In a few significant instances, this voice-over presence is provided by Fellini himself, something rendered moot when viewing prints dubbed in English. To define Amarcord as merely another "political" film would fail to do justice to such a poetic work. The film's title means "I remember" in one of the dialects of Fellini's native province, but this does not amount to a strictly autobiographical interpretation of work. While Amarcord, as its title suggests, contains a great deal of nostalgia, Fellini's use of nostalgia as a means of romanticizing the past serves to underline his belief that fascism was based upon false ideals, and also his recognition that regret or nostalgia is as inevitable as sentiment as refusal.

Thus, Fellini offers Amarcord not just as a political explanation for a dark period in Italy's national life but as an important clue to the understanding of Italian national character as well. Though the film denounces the state of perpetual adolescence, and illustrates Fellini's belief that refusal of individual responsibility characterizes Italian society, it never degenerates into dogmatic treatise. Instead Amarcord performs a certain magic that only a master of the cinema could accomplish.

Peter Bondanella is the chairman of West European studies

at the University of Indiana at Bloomington,

and is the author of The Cinema of Federico Fellini (Princeton)

Fellinis Entwurf der »Rex«

Un autre film extraordinaire de la part d'un cinéaste pour qui tourner semble terriblement facile: c'est sa seconde nature. Amarcord (le titre signifie Je me souviens) se veut une autre oeuvre en partie autobiographique, extrêmement vivante, comme tous ses longs métrages. Fort bien reçu à sa sortie, il demeure plus accessible que 8 1/2, par exemple, qui nécessite plus d'un visionnement. Encore plus humoristique que son cinéma habituel, Amarcord nous entraîne dans un tourbillon de gens pittoresques et de situations amusantes.

Se déroulant dans un village en Italie au cours des années 30, Amarcord progresse tel une anthologie d'histoires. En effet, le récit est divisé en de multiples petits épisodes. Nous suivons les aventures de divers individus habitant cette ville. Au début, après une courte introduction, nous faisons un séjour à l'école alors qu'on nous montre le tempérament légèrement délinquant des étudiants. Nous passons ensuite quelque temps au sein d'une famille où les deux parents sont en pleine querelle. L'aîné de la famille, pour sa part, désire expérimenter, tenter de nouvelles choses. Il est hypnotisé par Gradisca (Magali Noël), une femme aisée, très jolie.

Par la suite vient possiblement le segment le plus divertissant du film en entier (à mon avis): le famille en question va chercher le frère du père, soit l'oncle Téo (Ciccio Ingrassia). Il appert qu'il souffre d'une certaine maladie ne le rendant pas "normal" comme ses proches. En chemin, alors qu'il demande de s'arrêter pour se soulager, il oublie de dégrapher sa braguette, et, mal à l'aise, la famille accepte de le reprendre. Plus tard, il décide, subitement, de grimper dans un arbre. Le voilà donc, haut perché, criant à répétition: «Je veux une femme!». Son frère (Armando Brancia), le chef de clan, est au bout du rouleau. Il tente tout ce qui est en son pouvoir pour le faire redescendre, mais sans succès. Il devra appeler l'aide des médecins.

Par la suite vient possiblement le segment le plus divertissant du film en entier (à mon avis): le famille en question va chercher le frère du père, soit l'oncle Téo (Ciccio Ingrassia). Il appert qu'il souffre d'une certaine maladie ne le rendant pas "normal" comme ses proches. En chemin, alors qu'il demande de s'arrêter pour se soulager, il oublie de dégrapher sa braguette, et, mal à l'aise, la famille accepte de le reprendre. Plus tard, il décide, subitement, de grimper dans un arbre. Le voilà donc, haut perché, criant à répétition: «Je veux une femme!». Son frère (Armando Brancia), le chef de clan, est au bout du rouleau. Il tente tout ce qui est en son pouvoir pour le faire redescendre, mais sans succès. Il devra appeler l'aide des médecins.

L'humour lors de ces scènes est merveilleux. Il est tellement évident que Federico Fellini a concocté Amarcord avec tout son coeur que les touches satiriques de son film sont fort drôles. Un ton bon enfant est présent durant la majeure partie de long métrage, alors que le réalisateur explore des mythes sur la religion, l'entraide, le sexe, l'éducation et l'amour, tout cela dans un seul et même drame.

Quelques aspects rendent Amarcord immédiatement caractéristique: à de multiples reprises, un narrateur parle directement vers la caméra, par exemple, nous apprenant des détails sur la vie en Italie. Plusieurs images, toutefois, seront familières aux amants de Fellini: son génie visuel est plus en forme que jamais, et les couleurs sont sublimes. La direction artistique est parfois hallucinante, penchant presque vers le surréalisme. L'immense qualité visuelle de ce film a tôt fait de gagner l'admiration des spectateurs, et l'excellente musique de Nino Rota (fréquent collaborateur sur les productions du réalisateur) ajoute un volet nostalgique aux développements.

Comme à l'accoutumée, la qualité d'interprétation est sensationnelle. Fellini avait le don de choisir des acteurs infiniment naturels, des gens prêts à se livrer entièrement devant la caméra. Ils sont tous brillants dans ce film, et je n'ai personnellement reconnu qu'un seul visage, celui de Magali Noël, que j'ai vue dans La Dolce Vita. Tous plus convaincants les uns que les autres, continuellement honnêtes, ils nous font passer un moment plus que satisfaisant devant le petit écran.

Bref, Amarcord est un film magique. En raison de sa facture simple et dépouillée, ce n'est pas un long métrage qui perdra les non-initiés à l'oeuvre de Fellini. Contrairement à 8 1/2, il ne nécessite pas absolument plusieurs visionnements pour tout assimiler (bien que de le revoir est toujours un plaisir). Plus contenu, c'est une production qui plaira également à ceux qui trouvent son réalisateur parfois un peu outrancier. |

|

Federico Fellini's warmly nostalgic memory piece examines daily life in the Italian village of Rimini during the reign of Mussolini, and won the 1974 Academy Award as Best Foreign Film. The film's greatest asset is its ability to be sweet without being cloying, due in great part to Danilo Donati's surrealistic art direction and to the frequently bawdy injections of sex and politics by screenwriters Fellini and Tonino Guerra. Fellini clearly has deep affection for the people of this seaside village, warts and all, and communicates it through episodic visual anecdotes which are seen as if through the mists of a favorite dream, playfully scored by Nino Rota and lovingly photographed by Giuseppe Rotunno. Amarcord is a rich gem of a film which only improves on subsequent viewings.

Federico Fellini's warmly nostalgic memory piece examines daily life in the Italian village of Rimini during the reign of Mussolini, and won the 1974 Academy Award as Best Foreign Film. The film's greatest asset is its ability to be sweet without being cloying, due in great part to Danilo Donati's surrealistic art direction and to the frequently bawdy injections of sex and politics by screenwriters Fellini and Tonino Guerra. Fellini clearly has deep affection for the people of this seaside village, warts and all, and communicates it through episodic visual anecdotes which are seen as if through the mists of a favorite dream, playfully scored by Nino Rota and lovingly photographed by Giuseppe Rotunno. Amarcord is a rich gem of a film which only improves on subsequent viewings.

semi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale, with an ethereal, dreamlike quality that combines sharply drawn memories with vividly engaging fantasy. Like William Wordsworth, Fellini implies that the child is father to the man, and Amarcord is a both a lament for and an homage to his hometown. Employing a picaresque style, Fellini expertly weaves the tales of a wild menagerie of characters in pre-WW II Italy. No mere sentimentalist, he also tackles the prickly issue of the emergence of Fascism. The film takes careful aim at fanatics, while conserving its empathy for the lost, questing, confused, and lonely individuals in its midst. The family at the center of it all, loosely based on Fellini's own, is a well-drawn melange of coarse, pathetic, colorful, clever, and cranky characters. While Fellini does not choose nostalgic sepia tones, he does shoot much of the film in muted colors that seem slightly out-of-focus, as if he were attempting to transport us into a dreamlike state. Blending scenes of pathos and humor, vulgar carnal desire and transcendent magical illumination (the peacock's standing in the newly fallen snow, spreading its magnificent plumage is this film's signature image), Amarcord [...] remains a triumph of personal filmmaking.

semi-autobiographical coming-of-age tale, with an ethereal, dreamlike quality that combines sharply drawn memories with vividly engaging fantasy. Like William Wordsworth, Fellini implies that the child is father to the man, and Amarcord is a both a lament for and an homage to his hometown. Employing a picaresque style, Fellini expertly weaves the tales of a wild menagerie of characters in pre-WW II Italy. No mere sentimentalist, he also tackles the prickly issue of the emergence of Fascism. The film takes careful aim at fanatics, while conserving its empathy for the lost, questing, confused, and lonely individuals in its midst. The family at the center of it all, loosely based on Fellini's own, is a well-drawn melange of coarse, pathetic, colorful, clever, and cranky characters. While Fellini does not choose nostalgic sepia tones, he does shoot much of the film in muted colors that seem slightly out-of-focus, as if he were attempting to transport us into a dreamlike state. Blending scenes of pathos and humor, vulgar carnal desire and transcendent magical illumination (the peacock's standing in the newly fallen snow, spreading its magnificent plumage is this film's signature image), Amarcord [...] remains a triumph of personal filmmaking.  Fellini at his ripest and loudest recreates a fantasy-vision of his home town during the fascist period. With generous helpings of soap opera and burlesque he generally gets his better effects by orchestrating his colourful cast of characters around the town square, on a boat outing, or at a festive wedding. When he narrows his focus down to individual groups, he usually limits himself to corny bathroom and bedroom jokes, which produce the desired titters but little else. But despite the ups and downs, it’s still Fellini which has become an identifiable substance like salami or pepperoni that can be sliced into at any point yielding pretty much the same general consistency and flavour.

Fellini at his ripest and loudest recreates a fantasy-vision of his home town during the fascist period. With generous helpings of soap opera and burlesque he generally gets his better effects by orchestrating his colourful cast of characters around the town square, on a boat outing, or at a festive wedding. When he narrows his focus down to individual groups, he usually limits himself to corny bathroom and bedroom jokes, which produce the desired titters but little else. But despite the ups and downs, it’s still Fellini which has become an identifiable substance like salami or pepperoni that can be sliced into at any point yielding pretty much the same general consistency and flavour. Twenty years after I Vitelloni, Fellini returned to Rimini. In Amarcord he calls on the free-spirited fantasies of his later films, as well as the bittersweet comedy and intimate sense of detail of his early films, to evoke a year in the life of this small Italian coastal town in the mid-1930s. Amarcord is filled with phantasmagorical gems from the director's imagination: a peacock flying through the snow alights on the piazza to signal the coming of spring; a child on his way to school encounters a herd of cows who are transformed by the early-morning fog into frightening monsters. But the film is also rooted in history, filtered through memory: focusing on one family of perfectly normal eccentrics, Fellini examines their impact on each other's lives and the impact of life on them through a series of interacting tales ("some romantic, some slapstick, some elegiacal, some bawdy, some … mysterious" Vincent Canby). Fascism was a fact of life and, for Fellini, a focal point around which to examine the community, the Church, the state and the family–all of the elements that made Mussolini's acceptance possible. Like his protagonist Titta, a man in his fifties in 1972, Fellini looks to the past in this film for "the source of our illusions, our innocence and our feelings." But for Fellini, it is also a catharsis: "I made Amarcord to finish with youth and tenderness," he has commented.

Twenty years after I Vitelloni, Fellini returned to Rimini. In Amarcord he calls on the free-spirited fantasies of his later films, as well as the bittersweet comedy and intimate sense of detail of his early films, to evoke a year in the life of this small Italian coastal town in the mid-1930s. Amarcord is filled with phantasmagorical gems from the director's imagination: a peacock flying through the snow alights on the piazza to signal the coming of spring; a child on his way to school encounters a herd of cows who are transformed by the early-morning fog into frightening monsters. But the film is also rooted in history, filtered through memory: focusing on one family of perfectly normal eccentrics, Fellini examines their impact on each other's lives and the impact of life on them through a series of interacting tales ("some romantic, some slapstick, some elegiacal, some bawdy, some … mysterious" Vincent Canby). Fascism was a fact of life and, for Fellini, a focal point around which to examine the community, the Church, the state and the family–all of the elements that made Mussolini's acceptance possible. Like his protagonist Titta, a man in his fifties in 1972, Fellini looks to the past in this film for "the source of our illusions, our innocence and our feelings." But for Fellini, it is also a catharsis: "I made Amarcord to finish with youth and tenderness," he has commented. [...] With AMARCORD, Fellini dropped all pretense of presenting a coherent plot, in favor of the impressionistic stylization and anecdotal narratives that had been increasingly dominating his work since the mid-60s. Never has the gallery of Fellini's cartoonish grotesqueries been more prevalent than in AMARCORD, from the hilariously feuding Biondi family with its irascible father, suicidal mother, crazy uncle, horny grandfather, and mischievous sons, to the motley group of local eccentrics—the blind, accordion-playing beggar; the bragging pushcart vendor; the elegant cinema manager called "Ronald Colman"; and of course, the marvelous assortment of women who are the objects of Titta's and his friend's fantasies—Volpina the animalistic whore, the Sophia Loren-ish Gradisca, and the freakishly endowed tobacconist, who has what's possibly the film's funniest scene, when she whips out her mammoth breasts to the astonishment of Titta, and the poor boy is practically suffocated by them and ends up sick in bed. Fellini takes all of these characters and creates a wonderfully riotous fresco of lust, vulgarity, and low comedy, yet infuses the various episodes with a sense of nostalgic lyricism, recalling the carefree days of innocent youth, when American movies overshadowed even Fascism and dominated one's dreams. (The local theatre is filled with pictures of Laurel and Hardy, Norma Shearer, et al., and Gradisca goes to see BEAU GESTE, and fantasizes about finding her own Gary Cooper.)

[...] With AMARCORD, Fellini dropped all pretense of presenting a coherent plot, in favor of the impressionistic stylization and anecdotal narratives that had been increasingly dominating his work since the mid-60s. Never has the gallery of Fellini's cartoonish grotesqueries been more prevalent than in AMARCORD, from the hilariously feuding Biondi family with its irascible father, suicidal mother, crazy uncle, horny grandfather, and mischievous sons, to the motley group of local eccentrics—the blind, accordion-playing beggar; the bragging pushcart vendor; the elegant cinema manager called "Ronald Colman"; and of course, the marvelous assortment of women who are the objects of Titta's and his friend's fantasies—Volpina the animalistic whore, the Sophia Loren-ish Gradisca, and the freakishly endowed tobacconist, who has what's possibly the film's funniest scene, when she whips out her mammoth breasts to the astonishment of Titta, and the poor boy is practically suffocated by them and ends up sick in bed. Fellini takes all of these characters and creates a wonderfully riotous fresco of lust, vulgarity, and low comedy, yet infuses the various episodes with a sense of nostalgic lyricism, recalling the carefree days of innocent youth, when American movies overshadowed even Fascism and dominated one's dreams. (The local theatre is filled with pictures of Laurel and Hardy, Norma Shearer, et al., and Gradisca goes to see BEAU GESTE, and fantasizes about finding her own Gary Cooper.) Filmed almost entirely on the soundstages and backlots of Cinecitta, the film is a triumph of studio artifice, with Fellini and his brilliant production designer Danilo Danoti and cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno creating a world of fanciful memory, producing one fantastic and poetic image after another: the Fascist rally with its gigantic "Il Duce" face made of flowers; the car bouncing up and down and its headlights flickering on and off as the boys masturbate and scream Jean Harlow's name; the row of female derrieres wiggling onto bicycle seats; the Arabian Nights fantasy with the 30 concubines in the swimming pool; the magical appearance of the luxury liner, with its twinkling lights set against a studio sunset; the peacock landing in the snow and displaying its dazzling plumage; and the wind blowing puffballs through the sky, which opens and closes the film. Poured on top of all this, like a fine sauce over delicious pasta, is one of Nino Rota's loveliest, bounciest scores, resulting in what is undoubtedly one of Fellini's greatest films.

Filmed almost entirely on the soundstages and backlots of Cinecitta, the film is a triumph of studio artifice, with Fellini and his brilliant production designer Danilo Danoti and cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno creating a world of fanciful memory, producing one fantastic and poetic image after another: the Fascist rally with its gigantic "Il Duce" face made of flowers; the car bouncing up and down and its headlights flickering on and off as the boys masturbate and scream Jean Harlow's name; the row of female derrieres wiggling onto bicycle seats; the Arabian Nights fantasy with the 30 concubines in the swimming pool; the magical appearance of the luxury liner, with its twinkling lights set against a studio sunset; the peacock landing in the snow and displaying its dazzling plumage; and the wind blowing puffballs through the sky, which opens and closes the film. Poured on top of all this, like a fine sauce over delicious pasta, is one of Nino Rota's loveliest, bounciest scores, resulting in what is undoubtedly one of Fellini's greatest films.  "The province of Amarcord is one in which we are all recognizable, the director first of all, in the ignorance which confounded us. A great ignorance and a great confusion. Not that I wish to minimize the economic and social causes of fascism. I only wish to say that today what is still most interesting is the psychological, emotional manner of being a fascist. What is this manner? It is a sort of blockage, an arrested development during the phase of adolescence… That is, this remaining children for eternity, this leaving responsibilities for orhers, this living with the comforting sensation that there is someone who thinks for you (and at one time it’s mother, then it’s father, then it’s the mayor, anoeher time Il Duce, another time the Madonna, another time the Bishop, in short other people): and in the meanwhile you have this limited, time-wasting freedom which permies you only to cultivate absurd dreams–the dream of the American cinema, or the Oriental dream concerning women; in conclusion, the same old, monstrous, out-of-date myths that even today seem to me to form the most imporeant conditioning of the average Italian."

"The province of Amarcord is one in which we are all recognizable, the director first of all, in the ignorance which confounded us. A great ignorance and a great confusion. Not that I wish to minimize the economic and social causes of fascism. I only wish to say that today what is still most interesting is the psychological, emotional manner of being a fascist. What is this manner? It is a sort of blockage, an arrested development during the phase of adolescence… That is, this remaining children for eternity, this leaving responsibilities for orhers, this living with the comforting sensation that there is someone who thinks for you (and at one time it’s mother, then it’s father, then it’s the mayor, anoeher time Il Duce, another time the Madonna, another time the Bishop, in short other people): and in the meanwhile you have this limited, time-wasting freedom which permies you only to cultivate absurd dreams–the dream of the American cinema, or the Oriental dream concerning women; in conclusion, the same old, monstrous, out-of-date myths that even today seem to me to form the most imporeant conditioning of the average Italian." All of the collective events in the provincial town during the Mussolinian era–the absurd classrooms taught by pedantic, incompetent, or neurotic professors; the visit of the Fascist federale on April 21 (the anniversary of the mythical foundation of Rome celebrated by the regime); the passage of the ocean liner Rex before an awed group of townspeople; the burning of the great bonfire to celebrate the pagan rites of springtime–are, for Fellini, "occasions of total stupidity," part of a gigantic leveling process which buries individuality in mass conformity before symbols of power. This is clearest in the imaginary Fascist wedding staged by Fellini before an enormous bust of Mussolini made of pink and white flowers: the entire population seems anxious to become a collective, unthinking entity under Il Duce’s benevolent gaze.

All of the collective events in the provincial town during the Mussolinian era–the absurd classrooms taught by pedantic, incompetent, or neurotic professors; the visit of the Fascist federale on April 21 (the anniversary of the mythical foundation of Rome celebrated by the regime); the passage of the ocean liner Rex before an awed group of townspeople; the burning of the great bonfire to celebrate the pagan rites of springtime–are, for Fellini, "occasions of total stupidity," part of a gigantic leveling process which buries individuality in mass conformity before symbols of power. This is clearest in the imaginary Fascist wedding staged by Fellini before an enormous bust of Mussolini made of pink and white flowers: the entire population seems anxious to become a collective, unthinking entity under Il Duce’s benevolent gaze.

Als der Regisseur in der Krise steckte und eine Zwangspause einlegen mußte, schrieb er den Essay Mein Rimini. Es ist ein sehr persönliches Buch, voller Kindheitserinnerungen, Anekdoten und Konfessionen. Aber auch mit exakten Ortsangaben, so daß man auf den Spuren Fellinis einen Rundgang durch die Stadt unternehmen kann. Vom Bahnhof, dem Ort der abenteuerlichen Träume, zum eleganten, um die Jahrhundertwende erbauten 'Grand Hotel', einem Märchen des Reichtums, des Luxus, des orientalischen Prunks, oder gleich zum Strand, wo die TouristenMassen in der Sonne braten. Nach dem Krieg, in dem viel zerstört wurde, ist Rimini zu einer gesichtslosen Ferien-Hochburg verkommen, doch schon als kleiner Junge beobachtete Fellini die Deutschen, die mit dem Daimler Benz ans Meer kamen (und im Wasser Dickwänste, Walrosse). Die eigentliche Stadt liegt auf der anderen Seite der Eisenbahnlinie. Das Kino 'Fulgor', das Federico in hitzigen Pubertätsträumen eine warme Kloake aller Laster schien, steht noch; es befindet sich gleich neben der Kirche Chiesa dei Servi. Seine Angaben über das Geburtshaus sind jedoch zu korrigieren: Laut Eintragung in die Einwohnermeldekartei wohnte die Familie Fellini damals in der Viale Dardanelli Nr. 10. Derlei Recherchen finden nicht den Beifall des Künstlers, der mit seinem Werk keineswegs den Fremdenverkehr ankurbeln will: Ich habe den Eindruck, zu einem Objeict des Tourismus geworden zu sein, dagegen lehne ich mich auf.

Als der Regisseur in der Krise steckte und eine Zwangspause einlegen mußte, schrieb er den Essay Mein Rimini. Es ist ein sehr persönliches Buch, voller Kindheitserinnerungen, Anekdoten und Konfessionen. Aber auch mit exakten Ortsangaben, so daß man auf den Spuren Fellinis einen Rundgang durch die Stadt unternehmen kann. Vom Bahnhof, dem Ort der abenteuerlichen Träume, zum eleganten, um die Jahrhundertwende erbauten 'Grand Hotel', einem Märchen des Reichtums, des Luxus, des orientalischen Prunks, oder gleich zum Strand, wo die TouristenMassen in der Sonne braten. Nach dem Krieg, in dem viel zerstört wurde, ist Rimini zu einer gesichtslosen Ferien-Hochburg verkommen, doch schon als kleiner Junge beobachtete Fellini die Deutschen, die mit dem Daimler Benz ans Meer kamen (und im Wasser Dickwänste, Walrosse). Die eigentliche Stadt liegt auf der anderen Seite der Eisenbahnlinie. Das Kino 'Fulgor', das Federico in hitzigen Pubertätsträumen eine warme Kloake aller Laster schien, steht noch; es befindet sich gleich neben der Kirche Chiesa dei Servi. Seine Angaben über das Geburtshaus sind jedoch zu korrigieren: Laut Eintragung in die Einwohnermeldekartei wohnte die Familie Fellini damals in der Viale Dardanelli Nr. 10. Derlei Recherchen finden nicht den Beifall des Künstlers, der mit seinem Werk keineswegs den Fremdenverkehr ankurbeln will: Ich habe den Eindruck, zu einem Objeict des Tourismus geworden zu sein, dagegen lehne ich mich auf. Die Reise in die Dimension der Erinnerung ist ein in der Vergangenheit spielender Tagtraum, notwendigerweise eine verrückte, lächerliche, komische und närrische Wiederbesichtigung von Situationen, Erlebnissen und Wahrnehmungen, die, oft nur unzusammenhängend, verzerrt und verzeichnet, aus dem Unbewußten auftauchen. Die erste Szene von Amarcord: Corso und Piazza eines Städtchens. Der Frühling kündigt sich an. Durch die Luft wirbelt die Manine, flockig-weicher Pappelsamen. Der Dorfdepp schnappt nach ihm, brabbelt eine unverständliche Erklärung vor sich hin. Was willst du uns sagen? Aus dem Off hört man Fellinis Stimme, die Erinnerung beschwörend. Statt einer durchgehenden Handlung entfaltet der Film ein Kleinstadt-Panorama als pittoresken Bilderbogen: der Provinzgigolo und der klatschsüchtige Friseur, die mondäne Schönheit und der skurrile Sonderling, die italienische Familie, in der laut und tennperamentvoll gestritten wird, Lehrer, Geistliche und Carabinieri, allesamt leicht groteske Gestalten, liebevoll gezeichnete Karikaturen. Die Provinz als Welttheater: Man spielt große Oper, doch es wirkt immer nur wie eine Operettenvorstellung. Der Junge Titta steht im Mittelpunkt, seine pubertären Träume und Sehnsüchte, diese seltsam erregenden und zugleich quälenden Momente, verwirrend und peinlich. Der Reiz des Verbotenen, die ersten sexuellen Abenteuer und hinterher die Schuldgefühle. Dabei spielt sich das meist nur in Gedanken ab. Als die Tabakhändlerin ihn an ihren gewaltigen Busen drückt, flüchtet er entsetzt zur Mama. Eine andere Episode variiert das Thema: Man unternimmt eine Landpartie, dazu wird der verrückte Onkel Theo aus der Anstalt geholt. In einem unbeobachteten Moment klettert er auf einen Baum und schreit: Ich will eine Frau. Anfangs amüsiert man sich darüber, doch nach einer Stunde stellt sich Ratlosigkeit ein. Vergeblich alle Versuche, ihn herunterzuholen — der Onkel sitzt in der Baumkrone und verlangt nach einer Frau. Erst als die zwergwüchsige Nonne aus der Anstalt kommt — sie verfügt über eine unerklärliche Macht —, genügt ein Satz, und der eben noch wütende Irre steigt gehorsam und sanftmütig vom Baum.